The Lord says, “Be still, and know that I am God;

I will be exalted among the nations,

I will be exalted in the earth.”

_____________________

If I were to ask someone for a contemporary definition of the word “leisure,” they would probably respond with something like this: “Leisure is free time meant to be used for personal enjoyment.”

If I pressed them to expound on that definition further, after pondering for a moment, they might suggest that the best way to define leisure is to say what it is not. They might then express some version of the notion, “leisure is the opposite of work.”

If I then instructed them to please succinctly define leisure using just a single word, a majority might be expected to come up with a word like “idleness.”

There is nothing revolutionary in these definitions. They are commonplace and well understood in the modern age.

The problem I have is this: I want to convince you that leisure should have a prominent place in the life of a Secular Franciscan.

Based on the above, that would be a hard argument to make. In these definitions, leisure has a distinctly worldly focus grounded in the freedom of an individual to do as she or he pleases, with little reference to restraint or responsibility. There is no mention of and no direct relationship to God. Worse than that, “idleness” is a synonym for sloth or acedia, one of the seven deadly sins.

Article Eleven of the OFS Rule instructs the professed to “seek a proper spirit of detachment from the temporal.” Indulging in leisure as defined above would seem to be in direct opposition to that. Article Sixteen states that we should “esteem work.” Again, leisure seems opposed.

But we need to understand that these definitions of the word “leisure” would have been unfamiliar to Francis and his brothers. Leisure had an entirely different connotation and tone in Italy in the early 1200s. If I am to persuade you that you need to embrace leisure as part of your Franciscan vocation, then I need to rediscover a meaning for the word that has been lost to today’s world, but that Francis would have known and understood intuitively.

The quote from the Psalm should give a hint as to the direction we are headed.

_____________________

The book that suggested this set of reflections to me is entitled Leisure, the Basis of Culture. The author is Josef Pieper, a German Catholic philosopher (born 1904, died 1997). Pieper originally presented this material as a series of two essays/lectures in 1947 post-war Germany.

At that time, Germany was emerging from their defeat in World War II. The entire society was engaged in a rebuilding effort. This renewal effort was not just physical. It was also spiritual, philosophical and metaphysical. Yes, the country needed to figure out how to meet day to day material needs on a permanent and ongoing basis, but it also needed to redefine its essence. The people had to be united in a mutual vision of what the future would look like. To best meet ordinary, everyday needs, the country needed to develop a common, shared understanding of the fundamental nature of reality, existence, truth and knowledge.

In the second paragraph of the work, Pieper puts it like this:

“to build our house (i.e., to rebuild the country), we must put in order again our entire moral and intellectual history.”

He then states emphatically,

“before any detailed plan along these lines can succeed, our new beginning, our re-foundation, calls for ….. a defense of leisure.”

Take a moment to decide whether that second statement makes sense to you? Is leisure fundamental to developing a cohesive and meaningful philosophy of existence? If the definitions of leisure given above are the reference, it would seem not. Or, if it does have a role, it might be along the lines of, “One needs a certain amount of downtime, a certain amount of leisure, to recharge their batteries. Leisure is needed if I am ultimately to be as productive as possible.” Leisure is at best an ancillary support to work.

To the contrary, Pieper places leisure first. The second quote indicates it as the starting place for the efforts at hand. The title of the book, Leisure, the Basis of Culture, confirms this assertion. Leisure is not meant to be an afterthought, subservient to work. The logic of that title suggests that leisure is pre-eminent, and that work can only have proper meaning in relation to a proper understanding and exercise of leisure.

Clearly, Pieper has an entirely different definition of “leisure” in mind. What definition is he working from? Could that definition be one that is sympathetic to and supportive of the Franciscan charism? If I understand what Pieper is hinting at, will that help me live out my profession more successfully?

To begin to understand where Pieper is coming from, we must delve a little deeper into the circumstances of post-war Germany. With the country in a process of complete renewal, there is a great expectation that everyone must do their part for success to be achieved. The amount of work that needs to be done is enormous and extraordinary. In that context, it is easy to understand how work would be seen as the primary concern. Anyone engaged primarily in leisure at this time would immediately be accused of not pulling their weight.

To engage in leisure in the modern sense, given the effort required for a successful rebuild, would be seen by most as an immoral act.

This leads to every activity in post-war Germany being redefined in terms of work. Prior to the war, the study of Philosophy would have been seen as a leisure activity. To lift a quote from Heraclitus from the text, Philosophy and the other Liberal Arts were seen as “listening-in to the being of things.” Being a philosopher was not an endeavor filled with activity. It did not involve “hammering out” ideas. Those who taught in a university or wrote books about the Liberal Arts would not have been labeled as “workers.” They would have been seen as part of an elite class who had the privilege of making a living “at their leisure.”

Pre-war, the Liberal Arts were more about being quiet and still and attending to Creation rather than using mental acumen to actively discern or in some way conquer the nature of Creation. Inspiration, revelation and grace would have been more relevant to the definition of a philosopher than discovery accomplished by the vigorous or even assaulting will of a man.

Philosophy had to be an important and necessary part of the rebuilding effort. A coherent and standardized metaphysical philosophy would serve as a great unifier for the people. But it could only be countenanced if its authors were translated from the world of leisure to the world of work.

So, to be made acceptable in the context of the work of rebuilding, the Liberal Arts were redefined as “intellectual work.” Given the framework of already established philosophical movements present both before and after the war, this redefinition became more than just a matter of semantics. It was put into actual practice. Philosophers began to rely more on their own intellectual acuity and less on inspiration as they practiced their craft.

The redefinition of the Liberal Arts away from listening and to active work then led to a redefinition of knowledge. Inspiration, grace and revelation lost eminence as sources of knowledge. The more man actively used his will and reason to search for knowledge and truth, the more convinced he became that nothing can be known or true unless it can be proven so by human logic and intelligence. The idea that one can “listen-in to the nature of creation” became passé, and, in many quarters, tawdry and unacceptable. Only that which could be proven by the human mind could be accepted as knowledge.

The book puts it like this:

To Kant, the human act of knowing is exclusively “discursive,” which means not “merely looking.” “The understanding cannot look upon anything.” …… In Kant’s view, human knowing consists essentially in the act of investigating, articulating, joining, comparing, distinguishing, abstracting, deducing, proving – all of which are so many types of active mental effort. According to Kant, intellectual knowing by the human being is activity, and nothing but activity.

In other words, human knowing is possible only through work. And the philosopher therefore is a worker just like everyone else.

Given this, we can see how the present definition of leisure developed. If work is conclusive and listening obsolete, then a definition of leisure based in listening is also outmoded. Instead of leisure and work complementing each other, they become opposed, and the definition of leisure evolved to become the opposite of work.

We can even see how leisure, in the modern context, developed a certain undesirable connotation. In the added introduction to my copy of the book, written in 1998, that negative inference is expressed like this:

“For the puritan, leisure is a source of vice; for the egalitarian, a sign of privilege. A Marxist regards leisure as the unjust surplus, enjoyed by the few at the expense of the many. Nobody in a democracy is at ease with leisure, and almost every person will say that he works hard for a living.”

_____________________

Now that we have some sense of the modern definition of leisure and the circumstances that brought it into being, we can refocus our efforts on our primary task. What is the definition of leisure that Pieper is advocating, and will that definition help us better understand and live out our profession to the Franciscan charism?

Let’s start our search by noting that the Greek word for leisure is “Scholé.” In Latin, the word is “Scola.” In English, the translation becomes “School.” In the ancient world, leisure and learning were not just complementary but intimately linked. Leisure had nothing to do with being idle. Instead, it was directed toward the pursuit of knowledge.

If the ancient root definition of the word leisure has to do with knowing, then the next step is to investigate how the ancients understood the act of learning.

Ancient philosophers like Aristotle and Plato did not dismiss discursive learning. However, they did not constrain access to the scope of human knowledge the way Kant does above. In ancient times, and in the medieval times that Francis lived in as well, a broad definition of the sources of knowledge was embraced. Attainment of knowledge through the type of discursive work that Kant champions had its place. But there was also much more room for intuition, grace and revelation than contemporary times and definitions allow.

Pieper presents this distinction like this:

Medieval thinkers distinguished between the intellect as ratio and the intellect as intellectus. Ratio is the power of discursive thought, of searching and re-searching, abstracting, refining, and concluding, whereas intellectus refers to the ability of simply looking, to which the truth presents itself as a landscape presents itself to the eye. The spiritual knowing power of the human mind, as the ancients understood it, is really two things in one: ratio and intellectus: all knowing involves both. The path of discursive reasoning is accompanied and penetrated by the intellectus’ untiring vision, which is not active but passive, or better, receptive – a receptively operating power of the intellect.

Without going any deeper into the presentation and arguments, we can begin to see how the ancient and medieval thinkers would then have identified the word “leisure.” Leisure becomes the conscious and deliberate act of learning by listening and being receptive to what our senses and our consciousness perceive separate from any deliberate, active work toward knowing that the mind might engage in.

Think about what it is like to look upon a rose. Without any effort at all, you can appreciate the beauty of its varied colors and form. If you lean in, you experience a delightful smell. If you gently touch the petals, the texture of the bloom becomes apparent. You might even experience a sensation of chalkiness if the pollen has blown onto the petals. If you are outside, a zephyr might cause the slightest movement, and you then become aware of the breeze on your cheek. A bee might enter the frame, and you can identify the buzz of its movement over the whisper of the wind.

You receive all these things through your senses, and your consciousness allows you to translate them into knowledge of the rose without engaging in any work at all. The inspiration contained in this experience constitutes knowing through the intellectus.

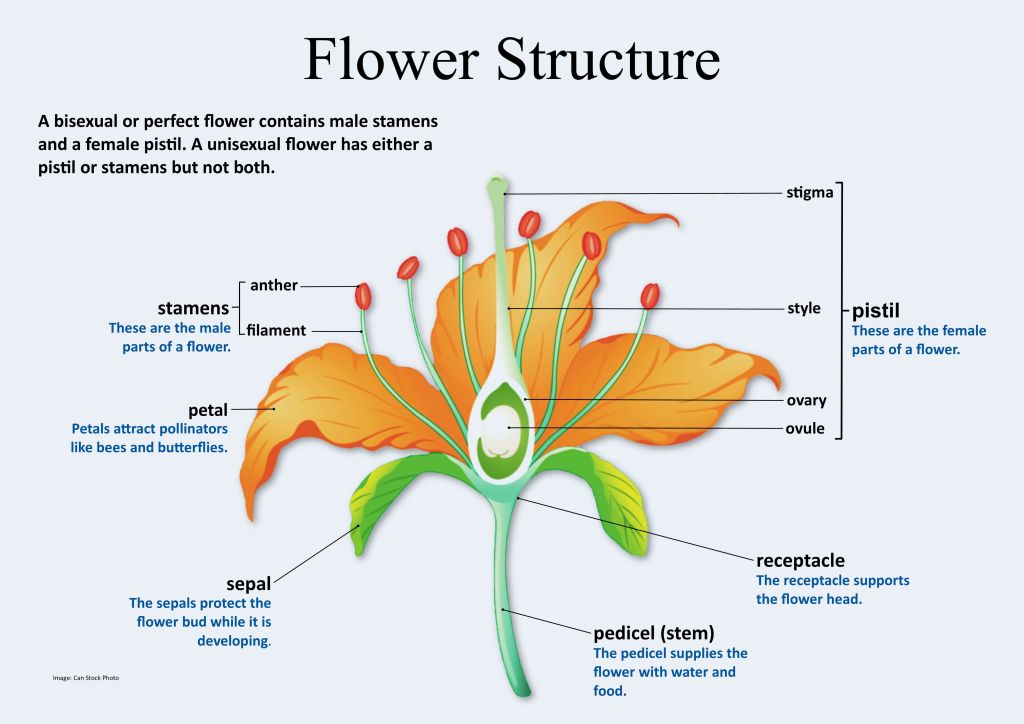

If you were a botanist, you could pick the bloom and identify the pistil and the stamen. With a little assist from inspiration, you can deduce the relationship between the breeze, the bee and the pollen. But to do this, you have now entered the world of work. The parts of the flower and the mechanism by which it reproduces are discovered and advanced through the investigative and deductive capabilities of the ratio.

Both human faculties are necessary if we are to fully know what a rose is. But it is downright depressing to think about only knowing the rose as collection of petals, pollen, pistil and stamen revealed by the ratio. What would we lose if we could not recognize the beauty of the infinite variety of colors and forms that flowers come in? How would the experience of walking through a field and encountering a patch of wildflowers be diminished if we could not feel the breeze on our cheek, hear the buzz of the bees working the patch, or smell the perfume of a flower we pick and share with a companion?

Pieper describes the act of knowing through the ratio as “decisively human” and the act of knowing through the intellectus as “surpassing human limits,” or “super-human.” He further says of intellectus that it allows us:

“to partake in the non-discursive power of vision enjoyed by the angels, to whom it has been granted to “take-in” the immaterial as easily as our eyes take in light or our ears hear sound.”

In other words, the intellectus gives us a window into the divine. It is the intellectus and the intellectus alone that experiences the inspiration, grace and revelation that are at the core and foundation of human knowing. It is even arguable that everything the ratio discovers is ultimately dependent on the intellectus. The ability to identify a pistil or stamen and discern its function within the overall concept of a flower originates initially in an inspiration that can only be sourced in the divine.

In the modern world, the activity of ratio has reached the point where it has become counterproductive. It has moved from being the partner of intellectus to fully suppressing it. Instead of helping us learn, it now impedes us. It obscures our imagination and therefore limits our ability to discover and know, especially about God and the mysteries He embodies. In an act of great irony, we have learned to follow Kant religiously. As a result, our knowing has become one-dimensional and stunted.

The ancient Greeks had no word that corresponds to our concept of everyday work. Instead, they described work as “not being at leisure.” This tells you everything you need to know about their priorities.

This set of priorities also existed at the time of Francis. The onset of the merchant class (Pietro Bernardone was certainly a worker) was one of the markers signaling the beginning of a slow transition to modernity. But Francis would still have embraced the pre-eminence of the intellectus. That inclination is what made him a willful troubadour in his youth, and the saint he became as he matured.

_____________________

We need to rediscover the importance of intellectus to our human condition. We need to learn once again how to be “not active.” We need to reacquire and then reassert the skills of receptivity and “listening to the being of things.”

The ability that Pieper has labeled intellectus is transcendent. At the same time, it is both not human and the highest fulfillment of what it means to be human.

That mystery itself can only be grasped by the intellectus, which is the locus where the spiritual and divine meet the ordinary and earthly. It is the place where a human touches the divine, however briefly and fleetingly, and learns Truths that the discursive work and reason of ratio cannot fully observe, comprehend or define.

And it is only possible to reach this place if we redefine leisure as the ancients understood it, and as Francis understood it.

- How often in your everyday life do you “stop to smell the roses?” How often are you too distracted, too busy and too caught up in everyday tasks and responsibilities to stop and appreciate the paradise that God has blessed you with?

- How much of your life is spent in the work of ratio? How much in the listening and the receptivity of intellectus?

- Is there proper balance in your life between the “decisively human” and the transcendently “super-human”?

If you are like me, the answer is, “I am out of balance. Way out of balance!”

I rely too much on ratio. I neglect intellectus almost entirely. I intentionally stop and metaphorically “smell the roses” only rarely, and when I do, I am almost always pulled back into busyness before I have learned anything.

The only way for me to correct this imbalance is to spend more time in leisure. But not leisure as understood by modern definitions. I need to spend time in leisure as it was understood by the ancients. I need to spend time in leisure as it was understood by Francis.

I need to learn to listen attentively. I need to be undistracted and available. I need to be more receptive to whatever it is that God wishes to teach me through all the faculties he has blessed me with. This includes work and reason, but it also includes the senses, my intuition and my imagination.

Most of all, I need to learn to see with not just my human eyes, but with my mind’s eye, the power of vision enjoyed by the angels.

In other words, as the Psalm intones, I need to “be still and know that He is God.”

One thought on “Rediscovering the Meaning of Leisure”